Remember that Part I is divided as follows:

PART I: LARRY RAY FOREMAN, AN AMERICAN OF DUTCH ANCESTRY

(1) Introduction

(2) “Nobody Emigrates Without a Promise!” The Ancestry and Origins of Larry Ray Foreman (1944-1999)

- Larry Ray Foreman Genealogy

- Historical Background to Nineteenth-Century Dutch Immigration to North America

- The Origins of Larry Ray Foreman

Larry Ray Foreman (1944-1999)

Now, let us continue with the first part of this essay. Let us together learn about the historical background of Dutch immigration to America and discover the origins and first steps of Larry Ray Foreman. Growing up in Orange City and Hull, Iowa, how was his early childhood like?

“We are of Holland descent; we cannot deny that fact;

but we consider ourselves Americans;

we are proud to descend from that noble Dutch race

(read [John Lothrop] Motley’s works);

but we are far prouder that we are now Americans,

that we can raise our children in the free air of this beloved Republic . . .”

Henry Hospers (1830-1901),

born in Hoog Blokland, Gelderland, The Netherlands,

was the founder, in 1870, of Orange City, Iowa.

The city of Pella, Marion County, Iowa was founded in 1847 by a group of 800 Dutch immigrants. This illustration represents the way Pella looked in 1848. Source: Memory of the Netherlands.

Historical Background to Nineteenth-Century Dutch Immigration to North America

The following is a historical narrative necessary to understand Dutch immigration in the United States. We need to have this historical background knowledge to be able to ask later questions about Dutch American identity and the life of Larry Ray Foreman. But, if you find this historical section too heavy a reading experience, you can skim it through and begin reading in earnest in the section titled, The Origins of Larry Ray Foreman.

Why did Dutch nationals emigrate to America in the nineteenth century?

Annemieke Galema says: “Nobody emigrates without a promise!” What were the Dutch immigrant’s expectations? Not being ourselves experts on Dutch emigration, for explanations, we turned to academic publications by historians who have specialized in the field of Dutch emigration to America: Robert Swierenga, Hans Krabbendam, Annemieke Galema, who has researched the transatlantic experience of the Frisian migrants (the boat trip itself usually lasting about two weeks or less), Michael J. Douma, Terence Schoone-Jongen, and David Zwart.

Robert P. Swierenga: Exodus Netherlands, promised land America. Dutch immigration and settlement in the United States. BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review 97.3 (1982): 517-537; and Place Mattered: The Social Geography of Dutch-American Immigration in the Nineteenth Century, Lecture delivered at Calvin College on November 17, 1998.

Hans Krabbendam: “But Tho We Love Old Holland Still, We Love Columbia More,” The Formation Of A Dutch-American Subculture In The United States, 1840–1920 in Going Dutch. Brill, 2008. 133-156;

Annemieke Galema: Frisians in Sioux County; from heitelân to Homeland, 1995;

Michael J. Douma: The Evolution of Dutch American Identities, 1847-Present, doctoral dissertation, Florida State University, 2011;

Terence Schoone-Jongen: The Dutch American Identity: Staging Memory and Ethnicity in Community Celebrations. Cambria Press, 2008; and

David Zwart: Faithful Remembering: Constructing Dutch America in the Twentieth Century, doctoral dissertation, Western Michigan University, 2012.

Motives for Dutch Emigration

Reasons to emigrate are always complex with many elements involved. But, for the case of Dutch emigration, we can generalize these elements by saying that the main “push” factors were a mixture of economic hardship, religious anxiety, and, to a lesser extent some political factors derived from religious conflicts in the Netherlands (especially in the late 1830s and in 1840s). The “pull” factors were the perceived opportunities in the United States of land availability and freedom or autonomy to practice their Calvinist religion and create communities centered on Christian values.

According to Robert Swierenga (1998), “Dutch emigration began in the mid-1840s in conjunction with an agricultural crisis caused by the failure of the potato and rye crops due to diseases, and the government persecution of religious Seceders from the State church. The confluence of these factors triggered an emigration movement among rural folk who had long suffered from poverty, land hunger, and a pinched future. Among Dutch emigrant family heads, 60 percent were farmers, farmhands, and day laborers. This was twice the national average.”

A Brief Historical Account of Dutch Religion

Now, because religion was an important element in Dutch emigration not only as one of the push factors but also as an organizing principle, and a source of leadership for the Dutch in America, we need to briefly explain some historical facts about religion in the Netherlands in the 19th century. The following paragraphs will offer a highly simplified version of this history.

Until the early 16th century Catholicism dominated Dutch religion but during the Protestant Reformation, mainly shaped by the theological ideas of John Calvin (1509-1564), the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederlandse Gereformeerde Kerk, NGK) emerged, and soon became the most important religion in the Netherlands.

In 1815, the territories of the former Dutch Republic/Kingdom of Holland, the Austrian Netherlands, and other territories gained independence from Napoleonic France. Then, the European powers that were in a coalition against Napoleon appointed Prince William of Orange and Nassau as the ruler of these territories, and, in turn, he adopted the title of “King of the Netherlands.”

William of Orange (1772 – 1843) became an authoritarian ruler. He proceeded to reorganize the NGK church creating a new top-down church hierarchy where he selected all church leaders. Some changes in the liturgy were implemented, and church laws now required the King’s approval.

This new church, called Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk (NHK) became the state church of the Kingdom. However, the new church structure was at odds with the traditionally decentralized Dutch Calvinist organization and led to many disagreements which grew in time. Many people were discontent with the NHK church and, in 1834, they left the church. Historically this event is called: the Afscheiding (“Instrument of Secession”).

This secession created a new church whose followers we will call the Seceders (in fact, this division created two congregations: the Christian separate communities (Christelijke afgescheiden gemeenten), and the Reformed Churches under the Cross, which, in 1869, merged into one church.)

A period of about ten years of religious intolerance and persecution followed which combined with economic and agricultural difficulties led some Dutch people to emigrate to America in the 1840s. “While the oppressive policies of the authorities had ceased by 1841, the Seceders expected little encouragement from the government” (Krabbendam, 2008).

Furthermore, in 1886, led by Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920), another split (called Doleantie) occurred in the official NHK church, thereby creating yet another church, the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands (GKN), which became the second largest Protestant church in that country.

The first log church in the town of Zeeland, Michigan, was founded by Albertus Van Raalte. Source. The United Archive of Holland.

The Dutch Churches in America

The Protestant Dutch immigrants brought with them their Calvinist religion (the official NHK and the Seceder church). But, upon arrival in America, these two branches of Dutch Protestantism suffered changes we cannot detail in this brief account.

“Whether of Seceder or Hervormde [NHK] background, many in the pioneer generation were radical Orthodox Calvinists who felt that their religious and cultural identity was under constant threat in the United States. Dutch immigrants were family-oriented and patriarchal, and ministers held an exalted place within their communities…. As Calvinists, the Dutch Americans naturally feared secularism and were suspicious of most forms of American religion, primarily the results-oriented Methodism. They desired to keep local control over their churches and keep their liturgy and worship clear of modern influences” (Douma, 2011; pp. 22-23).

Thus, for our purposes, suffice it to say that in America these two branches of Dutch Protestantism became: the Reformed Church in America (RCA), and the Christian Reformed Church (CRC). “These denominations also supported secondary schools, colleges, and seminaries that would provide the intellectual leadership for the community” (Zwart, 2012). For a deeper look into the schism between the RCA and the CRC, see the website A CHURCH DIVIDED. THE RCA-CRC SCHISM.

“Persistent inter-denominational quarrels led the RCA and CRC factions into steadfast positions, both stubbornly sure of the righteousness of their respective cause. The two groups disagreed on church order, public schooling, and the singing of hymns, but they generally agreed on the major doctrines of Calvinism. Dutch Americans from both churches united under a common ethnic identity based on a shared history and a shared faith” (Douma, 2011; p. 23). RCA communities tended to rely on the public school system while CRC communities created their own Christian primary and secondary schools (Schoone-Jongen, 2007).

The Seceder immigrants, although small in number compared with Catholic and NHK immigrants, were an important factor in Dutch immigration to America because of the strong leadership of some of their ministers and the role models they provided for new incoming immigrants.

In particular, two Seceder religious leaders became important organizers of the Seceder emigration to America: Rev. Hendrik Peter Scholte (1805-1868) and seminarist Albertus Christiaan van Raalte (1811-1876) (because of his critical points of view regarding the NHK church he was denied ordination. But, later, in 1836, he was ordained in the new Seceder church.)

Dutch settlements in Michigan. “The primary settlement field was within a fifty-mile radius of the southern Lake Michigan shoreline from Muskegon and Holland on the eastern side to Chicago, Milwaukee, and Green Bay on the western side” (Swierenga, 1982). Source: Wikipedia

Albertus van Raalte, in 1846, founded the city of Holland, Ottawa County, Michigan, and Hendrik Scholte the city of Pella, Marion County, Iowa. For further details, see Van Raalte and Scholte: A Soured Relationship and Personal Rivalry (Swierenga, 1997). The size of the two immigrant groups led by Van Raalte and Scholte had a maximum of eight hundred in each group (Krabbendam, 2008).

Other two important Seceder leaders were Reverends Jannes Vande Luyster (1789 – 1862), and Cornelius Vander Meulen (1800–1876) who, in 1847, following in the footsteps of Albertus Van Raalte founded the town of Zeeland, Ottawa County, Michigan. According to Hans Krabbendam (2008; pp. 138-139):

It is no wonder that religious leaders who had recently broken off from the established church took the lead in organizing the exodus across the Atlantic. They had gained experience in carving out a niche in Dutch society and had developed a broad set of usable skills.

For example, Rev. Cornelius van der Meulen (1800–1876) had worked as a laborer, contractor, and trader before he entered the ministry in 1838. Between 1841 and his emigration in 1847 he served a group of twelve struggling congregations in the province of Zeeland and guided them from weak beginnings to stable and self-supporting churches. He developed a broad perspective on the world and defended a practical church order geared for growth. Van der Meulen and his colleagues and a number of gifted lay people drafted a plan for future communities and took their valuable experience with them to the United States.

These provisions preselected immigrants; they were more than mere desperate people, they had a plan. The growth of strong social and economic ties within the United States reduced the chances of failure and reassured poverty-stricken migrants to take the risk.

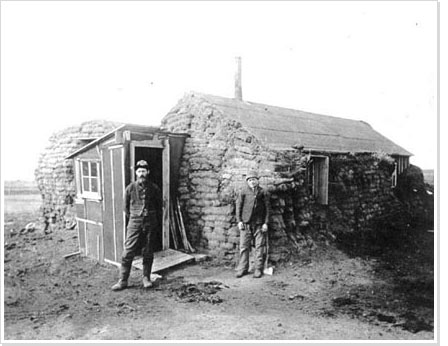

Early immigrant-made sod house in the prairie. Source: Memory of the Netherlands.

Few Netherlands Municipalities Were the Main Sources of Emigrants

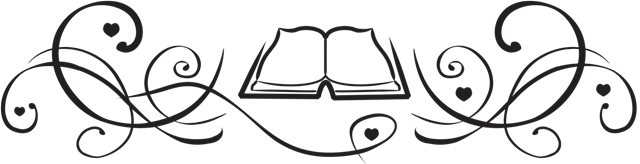

The Dutch in America clustered in a few regions, particularly around the Great Lakes and in some Midwestern counties in the States of Iowa and South Dakota. In the Netherlands, the emigrants originated in very few villages and municipalities (see the darker areas on the map below). A mix of religion-based culture and soil conditions were the most distinguishing characteristics of Dutch emigration patterns. “Culturally, the dominant Reformed regions north of the Rhine River and the southwestern islands sent out three-quarters of the emigrants. One-third of the Reformed emigrants were from Afscheiding villages” (Swierenga, 1982).

Of the 1,156 administrative units (gemeenten) in 1869–the equivalent of U.S. townships–only 134, or 12 percent, provided nearly three quarters of all emigrants in the period from 1820 through 1880; 55 municipalities (5 percent) sent out one-half of all emigrants; and a mere 22 municipalities (2 percent) furnished one-third of all emigrants…

….In the east the Gelderse Achterhoek on the German border early became a prime source region, as did the Veluwe east of the Zuider Zee. In the north it was the coastal farming regions of Groningen and Friesland; in the southwest the Zuid-Holland island of Goeree-Overflakkee and the three Zeeland islands; and in the southeast the Brabantse Peel centered in Uden…The culturally distinct Catholic provinces in the southern Netherlands, by contrast, had little overseas emigration. ….Considerably fewer emigrants, relatively, also left the urban provinces: Noord-Holland, Zuid-Holland, and Utrecht. (Swierenga, 1998).

The Main Motives Were Economics and a Desire to Have a Better Future

Even though, there are some Dutch-American accounts of the first emigration wave of the 1840s and 1850s that place the main motivating factor for emigration on religion. The table below (Dutch Immigrants by Religious Denomination) clearly shows that the majority of immigrants were not Seceders. Therefore, some other motivational factors must have been at play: “economics, more than religion, was the cause behind the New Immigration’s various waves.” (Schoone-Jongen, 2007).

| Dutch Immigrants by Religious Denomination | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Between 1835 and 1880 | 1849 | 1909 |

| NHK | 65% | 55% | 44% |

| Catholic | 20% | 38% | 35% |

| Seceder | 13% | 1.3% | 9.3% |

Data taken from Robert P. Swierenga’s ‘Faith and Family: Dutch Immigration and Settlement in the United States, 1820-1920‘ as cited by Terence Guy Schoone-Jongen in his doctoral dissertation (Schoone-Jongen, Terence G. Tulip time, USA: staging memory, identity and ethnicity in Dutch-American community festivals. Diss. The Ohio State University, 2007.)

Robert Swierenga (1982) explains that:

Soils are a key to emigration patterns. Dutch soils are broadly of three main types–clay, sand, and peat; and agricultural systems differed accordingly, as one might expect…. Heavy sea clays …predominated in the north of Groningen and Friesland, and in the southwest in Zeeland and the southern part of Zuid Holland. River clays are found along all the river systems. Farmers on the clay raised commercial grain crops for export, mostly wheat and corn. The farms were large and labor intensive.

The sandy loam soils of the eastern interior featured small family farmers who practiced the traditional three-field agriculture. In the sand dunes and heather along the western sea coast, farmers cultivated bulbs and flowers. The low-lying peat meadows ringing the Zuider Zee had good pasture grasses to support dairying, especially in southern Friesland. Another large peat area of thin soils ran along the German border of Groningen, Drenthe, and Overijssel.

I found that the clay soil areas of Zeeland, Friesland, and Groningen had heavy emigration, sandy regions had less, and peat meadows had almost none. The export crops on the clay soils suffered from growing international competition.

Dutch farmers could not compete with efficient North American farmers who could raise wheat far more cheaply on the fertile Great Plains. This forced Dutch commercial farmers, the “groote boeren,” to consolidate their holdings and buy new machinery to try to catch up with falling world prices. As a result, they laid off their day laborers and hired hands by the tens of thousands. The farm crisis reached epic proportions in the 1880s when Dutch emigration rates peaked.

Many farm laborers went to America in hopes of finding farm work and possibly climbing the agricultural ladder to farm ownership. They actually had little choice but to emigrate, because the Dutch industrial revolution had not yet begun in earnest and there were few factory jobs available.

The Coming of the Dutch to the Dakotas

As we shall soon see it, Larry Ray Foreman spent his early childhood in Hull, Sioux County, Iowa. But, when Larry Ray Foreman was thirteen years old, his family moved to Brookings, South Dakota, where he was to spend most of his youth. Now, how Dutch-influenced was his new environment?

To learn about Dutch emigration to the Dakotas, we consulted two articles from the South Dakota Historical Society: Gerald F. De Jong, The Coming of the Dutch to the Dakotas, South Dakota History (Vol. 5 (1), Winter 1974): 20-50; and Rex C. Myers, An Immigrant Heritage: South Dakota’s Foreign-Born in the Era of Assimilation, South Dakota History (Vol.19 (2), Summer 1989): 134-155; and one article from the Association for the Advancement of Dutch-American Studies, Brian Beltman (From Orange City to Harrison: Dutch Settlement in Douglas County, South Dakota, 2005).

The history of South Dakota is colored by many European ethnic settlements of Germans, Norwegians, Dutch, Danes, Russians, and Irish origins amongst a few others. “For many years the Dutch were reluctant to settle in the Dakotas. In 1860 when there were 310 foreign-born pioneers from nine European countries living in the Dakota Territory, none were Hollanders; and in 1870 they represented only eight of the territory’s 4,815 foreign-born” (de Jong, 1974). For the period 1890-1950, the South Dakota population born in the Netherlands was as follows: 1,428 (1890); 1,566 (1900); 2,656 (1910); 3,218 (1920); 3,068 (1930); 2,008 (1940); and 1,547 (1950) (Myers, 1989).

“Dutch-Americans learned about the availability of land in the Dakotas mainly from the Dutch language newspapers published in the United States. Of the approximately twenty such papers appearing at the close of the nineteenth century, De Volksvriend, published at Orange City, Iowa, was the most important. Also of influence were De Weekblad published at Pella, Iowa, and De Grondwel, published at Holland, Michigan” (de Jong, 1974).

South Dakota County Map. Source: Geology.com

“By 1885 there were about two hundred Dutch families residing in Charles Mix County in several towns and hamlets. The most important town was Platte, founded in 1883. Some of the names of the communities indicate the Dutch origin of their residents. Overijsel, later renamed Edgerton, located about seven miles southeast of Platte, was named after the Dutch province of Overijsel. Friesland, located about seven miles southwest of Platte, was another town whose name indicated where its residents originally hailed from in the Netherlands” (de Jong, 1974).

One of the most famous Dutch settlers in South Dakota hailed from Friesland, his name was Albert Hendriks Kuipers (1830-1904), born in Workum, Nijefurd, Friesland, who homesteaded in Charles Mix County. “Albert Kuipers was a very religious man and considered himself delegated by God to help the destitute people of the Netherlands find a new life for themselves in America” (de Jong, 1974).

People of Dutch ancestry also settled close to Brookings: “As late as 1902, for example, Hollanders, mostly from Iowa but also from Michigan, attracted by reports of lower land prices and cheap rent, began relocating in significant numbers at Volga, near Brookings.” (de Jong, 1974). Besides Charles Mix County, the other county with significant settlers of Dutch extraction was Douglas County. Gerald De Jong’s article includes a rich assortment of vintage photographs of Dutch settlements (portraying a farmhouse, churches, towns, and an immigrant-covered wagon train from 1900).

On Dutch-American identity

In the United States, people of Dutch ancestry tend to be called Dutch Americans. But, for many Americans of Dutch descent, their “Dutchness” identity can be very different. We should differentiate between:

(1) The descendants of the colonial Dutch (the founders of New Amsterdam which later became New York City);

(2) The mid-19th century Dutch immigration (1830-1880);

(3) The Dutch migration wave from 1880-1930; and

(4) The Dutch immigration that came during and after the Second World War.

Furthermore, for cases (2) and (3), we need to distinguish four categories: (i) the Catholics, (ii) the members of the NHK church, (iii) the Seceders, and (iv) the immigrants from Dutch regions having a unique language and culture like the West Frisians.

Dutch Catholics, because the churches they attended were multiethnic, assimilated quite easily into the American culture. On the other hand, “only the Calvinist Dutch Americans [NHK and Seceders] settled together in sufficient numbers to form cultural institutions that encouraged the long-term preservation of Dutch identity” (Douma, 2011).

They founded their churches and, for many years conducted religious services in the Dutch language, and their churches also doubled as schools and community centers. For the Calvinist Dutch Americans religion was part of their core identity.

Dutch-American 21st-century heritage celebrations held across the United States (like the Tulip festivals) are expressions of Calvinist Dutch Americans. Thus, when the media talk about Dutch Americans they are referring to Calvinist Dutch Americans.

Holland Michigan Tulip Time-Windmill Gardens. Source: Traveling Michigan

In other words, as Michael Duoma (2011) explains: “Dutch American identities were and are primarily a Protestant phenomenon. A core group of Dutch Americans formed a unique, conservative, and Calvinist subculture that existed across communities located principally in the American Midwest. These were non-radical immigrants who almost invariably joined churches instead of trade unions. As their ethnic communities endured into the twentieth century, they saw their Dutch heritage as an essential attribute for maintaining an authentic Christian faith. They believed strongly in God’s providence and in a religious calling by which God uses His people in the world. Dutch Americans believed they were among God’s chosen people.”

Now, as we have seen, the Dutch immigration also included a small number of Frisians who were also Calvinists. They tended to cluster together and create their associations separate from other Dutch immigrants.

“People from the province of Friesland, although content to be a political part of the Netherlands, have always considered themselves a separate ethnic and linguistic group, so it is not surprising to discover that, once residing in the United States, Dutch-Americans of Frisian background continued to proudly maintain their semi-separate identity by forming Frisian societies [like the Holland Frisian Society, Grand Rapids and Chicago Frisian Society chapters]” (Schoone-Jongen, 2008).

After the passing of the first generation regional allegiances among the Dutch “broke down and a general sense emerged of being plain Hollanders rather than Groningers, Drenthers, Gelderlanders, and Zeelanders. Frisians, of course, always remained Frisians” (Swierenga, 1998).

But, “the independent-minded Frisians dispersed themselves in America more than other Netherlanders. Their colonies were small and several lacked the glue of religious institutions to enable them to retard the inevitable process of Americanization” (Swierenga, 1998).

Having in mind that all generalizations are problematic, we can say that among the average traits of the Dutch-American culture we find that Dutch-Americans tend to be conservatives, very religious (devoutly Protestant), overwhelmingly Republican (yet, in 2005, when the commencement speaker at Calvin College, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, was President George W. Bush many faculties, students and alumni protested); they tend to have a no nonsense, honest, blunt, and upfront style of communicating; they love gardening (tulips!), eating all sorts of cheese and Droste chocolate, and baking especially cookies and, in particular, cookies in the shape of windmills (the word ‘cookie’ itself is a Dutch derived American English word from the Dutch word koekje); being of the Calvinist tradition and because messiness can be equated with sinfulness, there is a certain obsession with cleaning; Dutch American families are fond of wooden shoes (klompen), windmills, and Delft china; and across the United States in Dutch American enclaves, they held Dutch-American heritage celebrations like the Tulip festivals (in many cities like Holland, Michigan (since 1929); Pella, Iowa (1935); Orange City, Iowa (1936)), Dutch Smorgasbord in Harrison, South Dakota (1960), Dutch Festival in Edgerton, Minnesota (1950), and Dutch Days Festival in Fulton, Illinois (1974), among many others.

Michael Duoma (2011) has argued that the ethnic identity of Dutch Americans “has been resilient, not because it has remained intact, but rather because it has changed shape.” The peak of Dutch America was in the early 1900s. But, nowadays, for “many Americans of Dutch ancestry, however, “Dutchness” has little or no bearing on personal identity. ” For many Dutch Americans their “Dutchness” has faded away.

Now, we can ask the question: To what extent was Larry Ray Foreman’s personality influenced by the Dutch American culture? This question, however, is very difficult to answer as we did not have access to personal documents conveying his thoughts and ideas. Yet, there are few things we can say about it. But, we will delay answering this question until we present the results of our investigation on Larry Foreman’s origins.

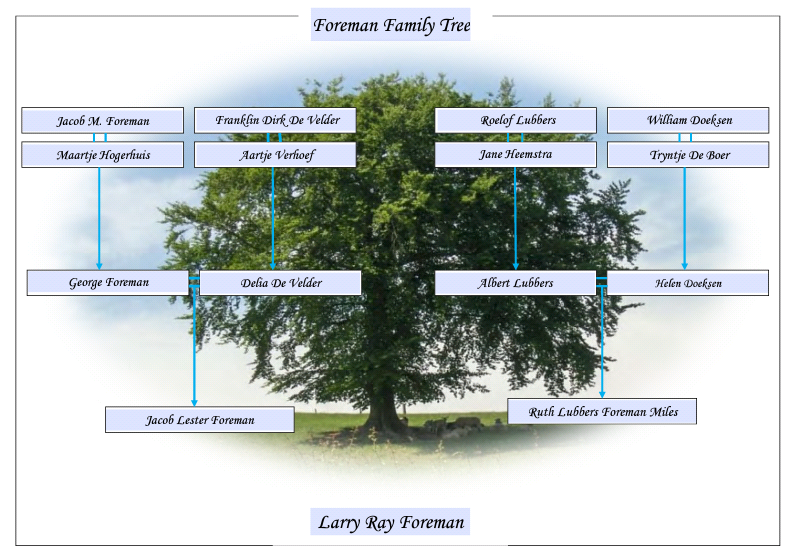

The Origins of Larry Ray Foreman

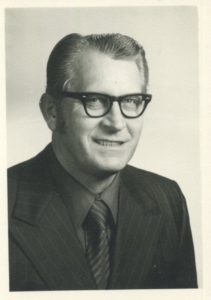

The parents of Larry Ray Foreman were Jacob Lester “Les” Foreman (1920-2011) and Ruth Jeane Foreman (nee Lubbers) (1921-2004). The couple married in Montgomery, Alabama, on November 7th, 1942, and Larry Ray Foreman was born to them on March 25, 1944, in Monroe, Louisiana. Larry Ray spent his baby and toddler years between military bases and the maternal and paternal hometown of Orange City, Sioux County, Iowa.

The baby Larry Ray Foreman with his father and paternal grandparents.

Larry Ray’s maternal grandmother, Helen (nee Doeksen) Lubbers also visited them. But, we found no pictures, just this newspaper notice.

Larry Ray Foreman’s first year birthday was celebrated ahead on March 16, 1945 in Orange City. His father was not present. Source: The Sioux County Capital, March 22, 1945.

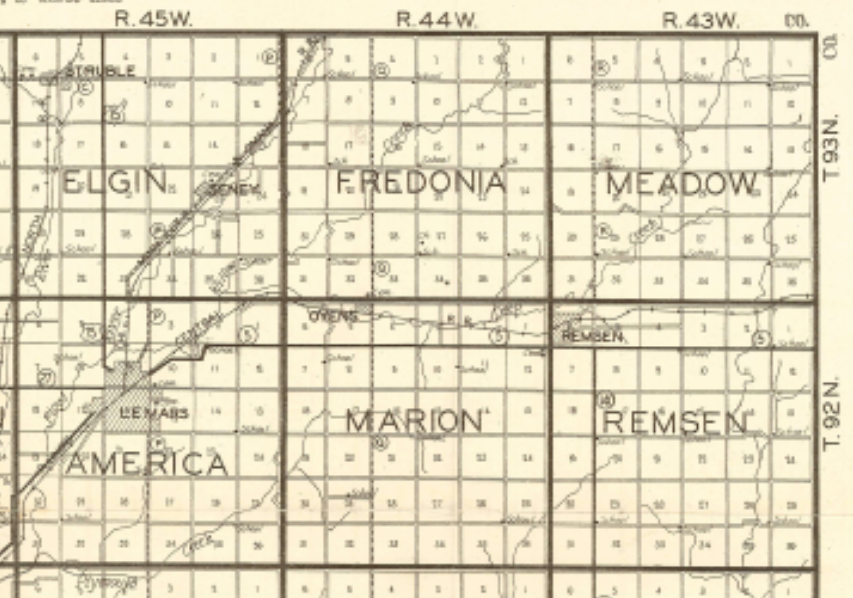

Map of Sioux County showing townships and towns. Source: Iagenweb.

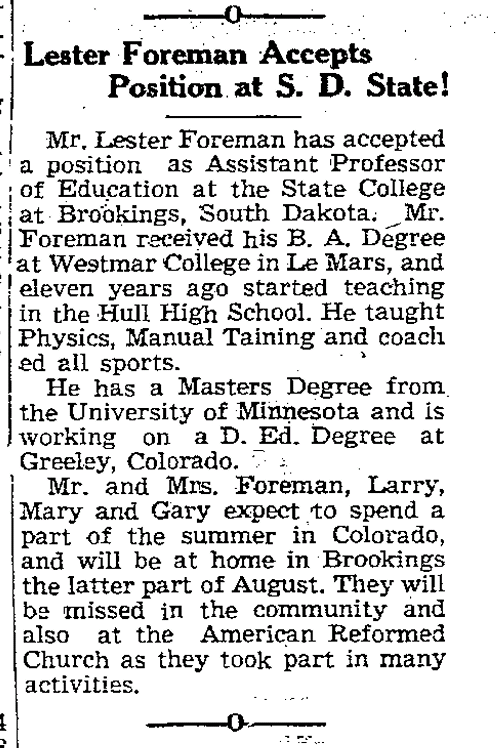

Larry Ray Foreman’s father: Lester Foreman

As stated on his birth record, Jacob Lester (Les) Foreman was born on January 4th, 1920, in Fredonia, Plymouth County, Iowa. (According to his obituary, he was born in Remsen, Plymouth County, Iowa; the townships of Fredonia and Remsen are located in rural areas and are very close to each other.)

Jacob Lester Foreman grew up in farms and when he was young he used to help his parents and siblings working on farm activities. In 1921, Jacob Lester’s father, George Foreman, rented farmland in Fredonia (for the farm location, see below).

In May 1938, Jacob Lester Foreman, better known by his second name Lester, graduated from Boyden High School in Iowa (today’s Boyden-Hull High School). In the graduation ceremony, he was awarded a scholarship by the school district superintendent E. I. Lack.

Boyden High School seems to us to be somewhat far away from the land property his father rented in Fredonia, Plymouth County in 1921. Maybe he attended Boyden High School because by 1934 he was staying with his maternal grandparents who lived on a farm just outside Boyden (see below), or maybe by 1934 his family had moved to another farm near Boyden or maybe he commuted to school from Fredonia.

Lester Foreman was a young man active in church-related activitities. For instance, in June 1938, together with other young adults led by Rev. John Pollock, he attended the Fiftieth Annual Convention of Young Peoples Christian Union at Goldfield, Iowa.

After graduating from Boyden High School in Iowa, Lester Foreman went on to study at Sheldon Junior College, in Sheldon, Iowa for two years before entering Western Union College in Le Mars, Iowa (in September 1951, Sheldon Junior College suspended its operations.) After he graduated from Sheldon Junior College, in addition to studying at Western Union College, he became one of the nine rural teachers in Center Township, Sioux County 1940-1941. He was responsible for district number 6.

When World War II started, Lester Foreman stopped studying at Western Union College and joined the Army Air Corps (formally known as the U.S. Army Air Forces, USAAF). He trained at several USAAF military bases to become a B-24 pilot and earned the rank of Lieutenant.

During World War II, USAAF established numerous airfields in Alabama and Louisiana for the anti-submarine defense of the Gulf of Mexico and training pilots and aircrews of, both, fighters and bombers. At that time, there were two major training bases: Maxwell Field, 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Montgomery, Alabama, and Selman Army Airfield, near Monroe, Louisiana (today’s Monroe Regional Airport).

After her marriage in 1942, it is our understanding, that Larry Ray’s mother, Ruth, traveled from base to base with her husband. Therefore, when Larry Ray Foreman was born in Monroe, his father could have been stationed at the Selman Army Airfield.

In February 1943, Jacob Lester Foreman was taking his basic training. He had only clocked 75 hours in the air, and he was stationed at the Squadron IV 72nd Army Air Forces Flying Training Division, Bush Field, Augusta, Georgia. Jacob Lester Foreman also spent time training as a pilot at a military air base in Liberal, Kansas. Towards the end of the war, on March 22nd, 1945, he was transferred to another air base in Lemoore, California.

Shortly after the war ended, Lester Foreman was discharged from USAAF. He then resumed his education at Western Union College and, in 1946, earned a B. A. degree from this institution (in 1948, Western Union College changed its name to Westmar College. “The original name, Western Union College comes from the union of western churches of the Evangelical church in 1900 which resulted in the founding of the school,” reads a newspaper notice in Hawarden Independent of April 15,th, 1948 announcing the name change. Westmar College was closed down in 1997).

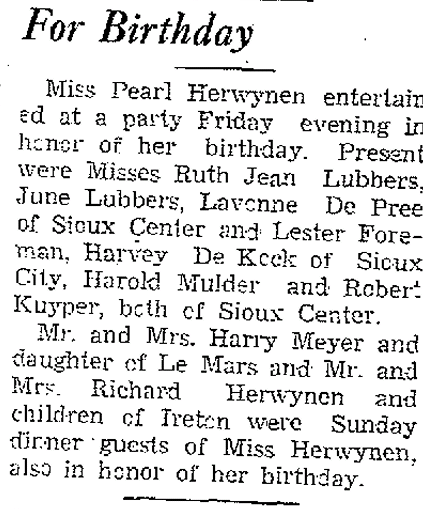

Lester and Ruth studied at high schools located in different places (Boyden and Orange City). They were both members of families of Dutch ancestry and their families were both members of the Trinity Reformed Church. We do not know when or how they both first met whether through church activities or family networks or, maybe, at Miss Pearl Herwynen’s birthday party on March 14th, 1941.

After he graduated from Western Union College, Lester Foreman soon found a job as a basketball coach at Hull High School in Hull, a town in Sioux County, Iowa where he also taught physics, industrial arts, and woodwork. On November 7th, 1946, the local newspaper The Sioux Center News announced that “Mr. and Mrs. Lester Foreman are moving to Hull where he is coach of the high school.” He was a quite successful basketball coach. By 1957, his “Class B Hull team had been in state tournament four times.”

Partial extract of public school news that appeared on Thursday, March 22, 1951, in The Sioux County Index.

Thus, the Foreman family settled down in Hull. Here, his wife, Ruth, eventually, got to serve as the town council clerk (from February 5th, 1952 to November 15, 1954) and keeper of the city jail. The young boy, Larry Ray Foreman, will spend the next ten years of his life in Hull, Iowa.

Lester Foreman continued furthering his education. He spent summers studying for graduate degrees. In 1950, he earned an M.A. degree from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis and, in 1957, after attending classes in six summer sessions and writing a doctoral dissertation, he earned a Doctorate of Education degree from the Colorado State College of Education in Greeley, Colorado (today’s University of Northern Colorado). The title of his doctoral dissertation in the field of educational administration was “School District Reorganization Plans for Sioux County, Iowa.”

In his life as a teacher, Lester Foreman taught every level from elementary country school to graduate education courses. In September 1957, he became Assistant Professor of Education at South Dakota State College (on July 1st, 1964, it became the South Dakota State University (SDSU)), and, he, eventually, also became the President of the South Dakota Education Association.

News of the Foreman family moving to Brookings, South Dakota. Source: The Sioux County Index, May 23, 1957.

The Religion Affiliations of the Foreman Family

Before continuing our description of Larry Foreman’s genealogical tree, it is convenient to make a stop to explain, without going into too much detail, the religious affiliations of the Foreman family. The great grandparents Jacob M. Foreman and Roelof Lubbers belonged to the First Reformed Church of Orange City, which is an active church in the Reformed Church in America. This church was created in 1871 to serve the Dutch settlers who founded Orange City. At that time, and for many years, the worshipping language of the church was Dutch. The transition from worshipping in Dutch to worshipping in English in this church occurred between 1925 and 1960 when the pastor of the church was Rev. Dr. Henry Colenbrander (1885-1963).

This church birthed several daughter churches in northwest Iowa among them the American Reformed Church of Orange City in 1885, the Trinity Reformed Church of Orange City, in 1919, and one college.

A postcard showing three Orange City churches, two affiliated with RCA and one affiliated with CRC. Source: Anderson, Doug, et al. Orange City. Arcadia Publishing, 2014, p. 22.

To accommodate in the RCA denomination an already Americanized population of Dutch ancestry who felt more comfortable using English than Dutch, the English-language American Reformed Church was created in 1885. As the Orange City population grew (320 people in 1880 to 1,662 in 1920) so did the number of churches, and for the same worshipping language reasons, after the First World War, the Trinity Reformed Church was established as yet another English-language church.

In addition, on July 19, 1882, in Orange City, to educate young people in the community for college and ministry in the RCA, the First Reformed Church leaders established the Northwestern Classical Academy, with the motto “Deus est lux” (God is light). In 1928, it became the Northwestern Junior College and Academy which today is the Northwestern College.

The second generation, George Foreman and Albertus Lubbers were members of the Trinity Reformed Church of Orange City. Therefore, when they were youngsters, Jacob Lester Foreman and Ruth Jeane Lubbers, the parents of Larry Foreman, should have also been members of the same Trinity Reformed Church. In addition, Larry Ray’s mother Ruth Jeane Lubbers is an alumna of Northwestern Junior College.

This change from the First Reformed Church in the first generation to the Trinity Reformed Church in the second generation is, we think, a signal of a deeper degree of acculturation of the Foreman and Lubbers families to American society.

Finally, when Jacob Lester and Ruth Foreman moved to Hull, they became members of the American Reformed Church of Hull. Therefore, Larry Ray Foreman’s religious tradition is within the RCA.

George Foreman, Larry Ray’s paternal grandfather

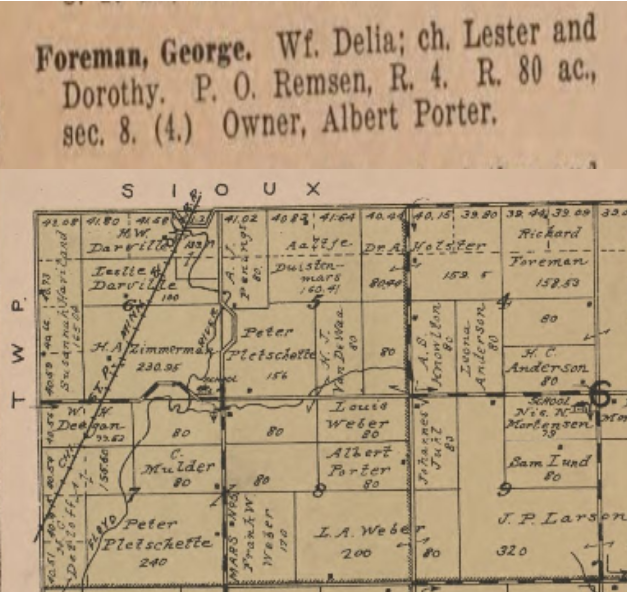

In turn, Jacob Lester Foreman was the son of George Foreman (1897-1985), a farmer, born in Elgin, Plymouth County, Iowa, on December 3rd, 1897, and Delia Foreman (nee De Velder) (1900-1962), born in Middleburg, Sioux County, Iowa.

A picture of Larry Ray’s paternal grandfather George Foreman with his family. In the middle, George Foreman (1897-1985) and his wife Delia Foreman (nee De Velder) (1900-1962). Top row: Jacob Lester ‘Les’ Foreman (1920-2011) (Larry Ray’s father) (left) and Donald Glen Foreman (1925-2014)(right). Bottom row: Larry Ray’s aunties: the sisters, Marjorie Mae Foreman (1924-2005) (left) and Dorothy Eileen Foreman (1921-2016) (right). When the United States entered World War II, both brothers joined the military.

According to Iowa Marriage Records, George married Delia De Velder on October 2nd, 1919, in Woodbury, Iowa (his obituary gives October 3rd, 1919, and Boyden for his date and place of marriage, respectively). The Alton Democrat newspaper of October 18th, 1919, under the title heading “Boyden News”, carried the following notice: “Miss Delia DeVelde [sic] and Mr. George Foreman were united in marriage at Sioux City, Iowa, recently. The news came as a surprise to their many friends.” Sioux City is in Woodbury County.

At the time of his World War I Draft Registration (April 12th, 1918), when George Foreman was 20 years old, he stated he was a farm laborer working for Ani Reckers in Orange City.

According to his obituary, throughout his life, George Foreman farmed in different places: Le Mars, Carnes, Boyden, and Orange City areas. We were only able to find evidence of his farming in Fredonia. From the Farmer’s Directory of Fredonia Township, we know that, in 1921, George Foreman, who by then was already married, rented 80 acres of land owned by Albert Porter in Fredonia Township.

George Foreman passed away on March 8th, 1985, in Orange City, Iowa. He was a member of the Trinity Reformed Church. But, when he was growing up, he must have attended church services at the First Reformed Church and listened to the pastor’s sermons in Dutch. How well did he know Dutch or Frisian? We do not know. Maybe the language he heard spoken at home was Frisian.

In 1921, George Foreman rented 80 acres from Albert Porter. Source: “Farmers’ Directory of Fredonia Township” and “Map of Fredonia Township” in Atlas of Plymouth County and the world (1921).

Regarding Delia’s parents, they were Franklin Dirk De Velder and Aartje (nee Ver Hoef) De Velder, both born in Pella, Marion County, Iowa.

Franklin Dirk De Velder (born on March 23rd, 1872, in Pella, died on January 12th, 1948, in Orange City) grew up in Harrison, South Dakota. He married Aartje Ver Hoef on March 13th, 1895. For one year they lived in Harrison, and, then, they moved to Iowa. They first lived near Middleburg, where her daughter Delia was born on January 17th, 1900. Some years later they moved to a farm near Boyden. Aartjie De Velder, born on October 16th, 1870, in Pella, died in 1943, and Franklin Dirk De Velder spent the last seven years of his life in Orange City. He was a member of the First Reformed Church in Orange City.

In 1923, we find him living outside Boyden on a 160-acre farm he owned.

According to the Atlas of Sioux County (1923) Franklin Dirk De Velder owned a 160-acres farm in the vecinity of Boyden, Sheridan Township, Plymouth County, Iowa.

The paternal great-grandfather of Larry Ray Foreman: Jacob M. (Fokkeman) Foreman

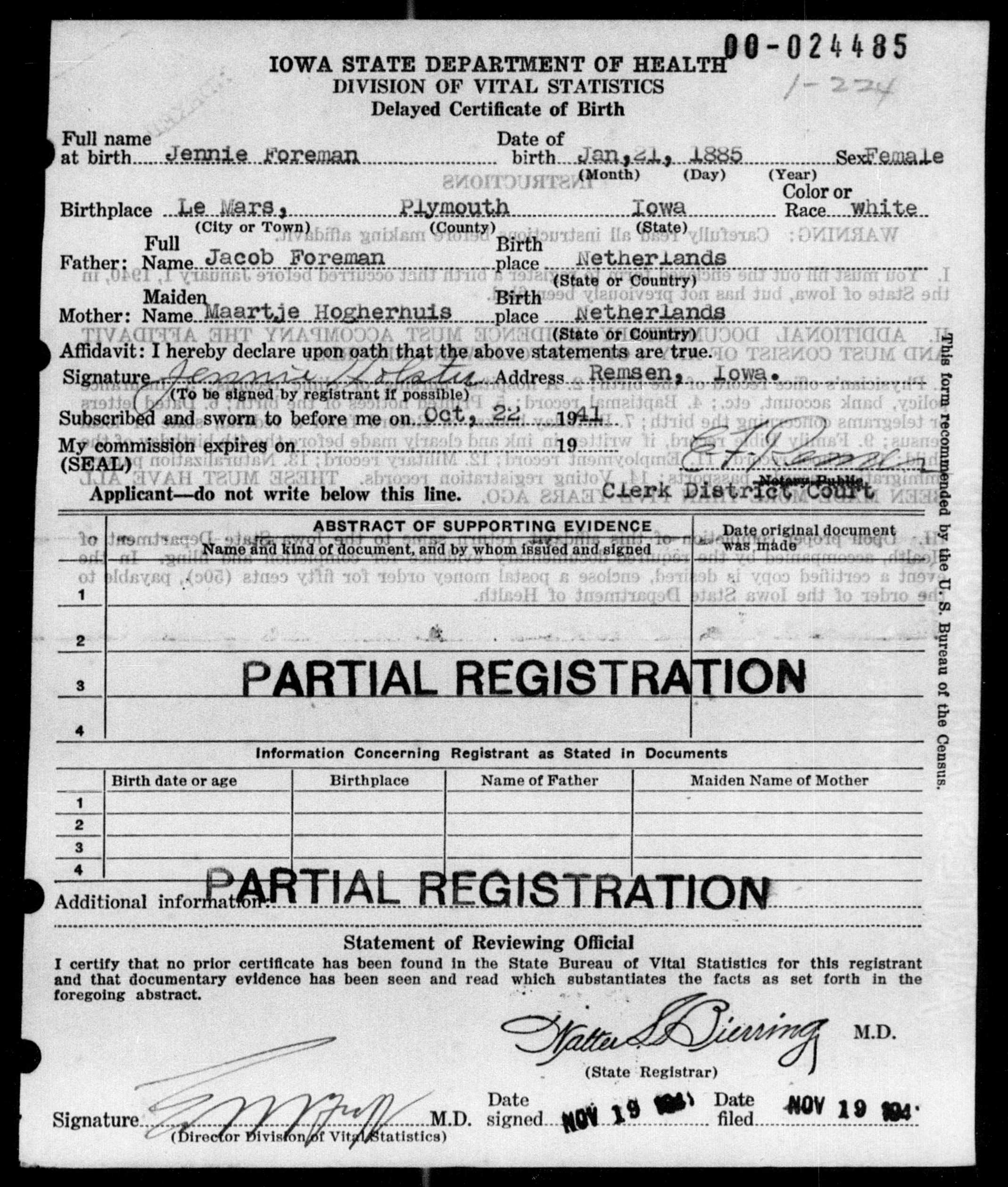

As to George Foreman’s parents, they were Dutch immigrants: Jacob M. Foreman and Maartje Hogerhuis (her last name also appears written in some records as Hogherhuis and her first name as Martje).

The population census of 1930 asked the question “Age at first marriage”. The age shown for Jacob M. Foreman is 21 years old. So, according to this census data, it follows that he married for the first time in 1876. On the other hand, the schedule of the 1920 population census indicates that Jacob Foreman lived with his wife and his mother-in-law, Dora Hogerhuis, then 95 years old, and list their years of immigration to the United States as 1882 for Jacob, 1883 for Maartje Hogerhuis, and 1884 for Dora Hogerhuis.

If Jacob Foreman only married once, then, he married Maartje Hogerhuis in the Netherlands in 1876, emigrated in 1882, and brought his wife from the Netherlands in 1883.

But, on the other hand, if his marriage to Maartje was his second wedding, then he met his future wife in America in 1883 and in that year got married. Jacob’s obituary mentions that he got married in 1883. If so, it thus follows that the Dutch immigrant couple met and married in America. However, we could not find an official record of their marriage. This information might be wrong but, today, we do not have conclusive evidence. This is a point that needs more research.

Together they had four children: Jennie (1885-1969), Henry (1888-1906), Michael “Mike” Jacob (1891-1953), and George Foreman (1897-1985). Michael Jacob’s birth record states that he was born on December 19, 1891 (his obituary indicates 1892 as his year of birth.)

According to the Dutch genealogy website, Jacob M. Foreman (his middle name is given as “G” instead of “M”) was born on January 16th, 1855, in Franeker, municipality of Franekeradeel, Friesland, Netherland. But it mistakenly indicates that he died in 1895 when he was 39 years old. On the other hand, his online obituary, which also states that he was born in Franeker, in a conflicting way, on its header section, it also says that he was born in Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden Municipality, Friesland, Netherlands, and it only mentions his birth year (1856). Having looked at census data, we can only say he was born in 1855.

Regarding Maartje Hogerhuis, unfortunately, so far we only know that she was born in the Netherlands in 1863 and that she died on April 30th, 1923 in Orange City, Sioux County, Iowa.

Our online research did not find out how Mr. Jacob M. (Fokkema) Foreman made his trip from Frisia to America. We only know that he landed in Iowa in 1882. We did not look deep enough into his case. To what Frisian network did he belong? What was his transatlantic voyage like? Did he enter America by the port of New York, Boston, or Philadelphia? Did he board a ship in Rotterdam or Antwerp? We do not know. Nor we were able to find out about his religious affiliation in the Netherlands (NHK or Seceder).

However, we can guess that he was affiliated with the Reform church (NHK) like the two Frisian individuals bearing the surname Fokkema we found in Pieter van Reenen’s list of Dutch immigrants in the city of Pella, Marion County, Iowa.

Jacob Foreman died in Orange City, on April 4th, 1941. In his obituary, it is said that his funeral services were held at the First Reformed Church of Orange City with Rev. Collenbrander officiating. The First Reformed Church is affiliated with the Reform Church of America (RCA), and, as it is well known, once in the United States, the majority of NHK members joined the RCA.

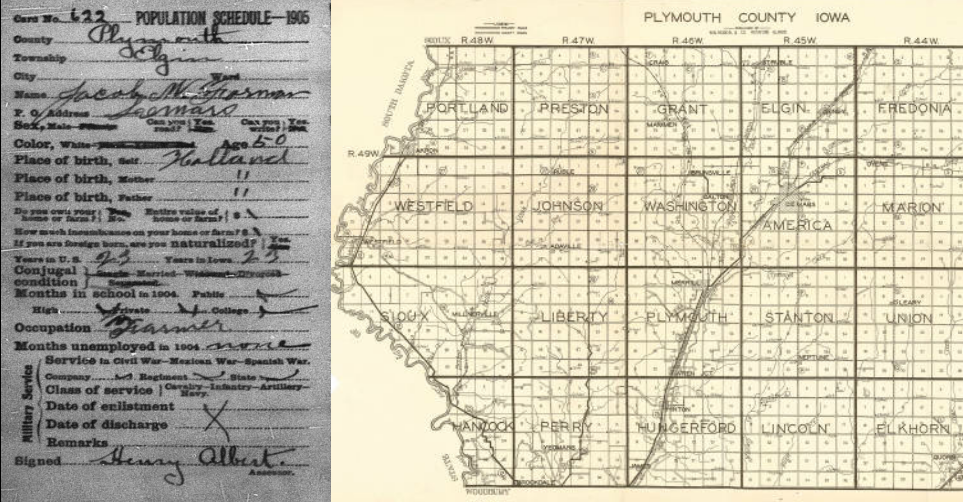

We also know that, in 1905, Jacob Foreman was living as a farmer in Elgin Township, Plymouth County, Iowa, in a property he rented, and his postal address at that time was in the nearby city of Le Mars (Township America). Plymouth County has a total area of 864 square miles (2,240 km2), and, in 1900, it had a population of 22,209 people.

Fifteen years later, in 1920, he was living in a house he owned in Orange City, Holland Township, Sioux County, Iowa. From the 1920 census data, we gather that he learned to speak English, and that, in 1887, he and his wife had naturalized as an American citizen.

Twenty-five years later, in 1930, he was still living in Orange City in a $2,000-worth house he owned. By then he was already a widower, 75 years old. His wife Maartje had died on April 30th, 1923. According to the census data, in the same house there also lived a housekeeper named Pristje Steensma.

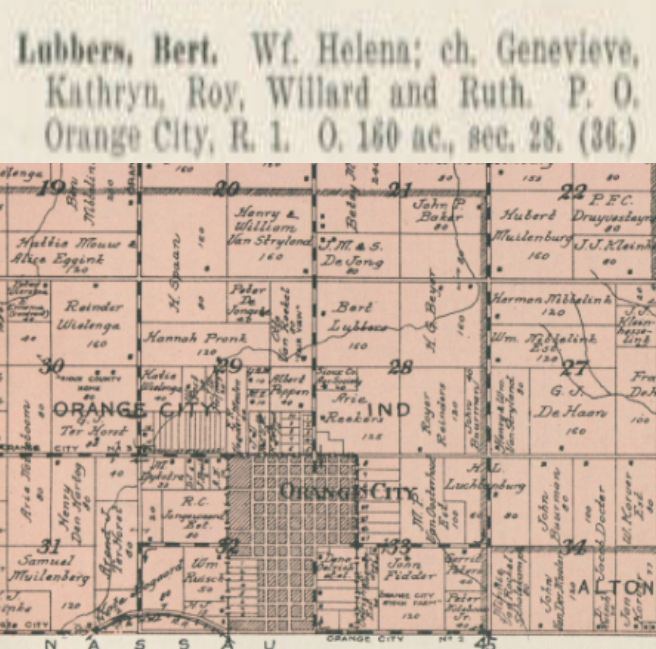

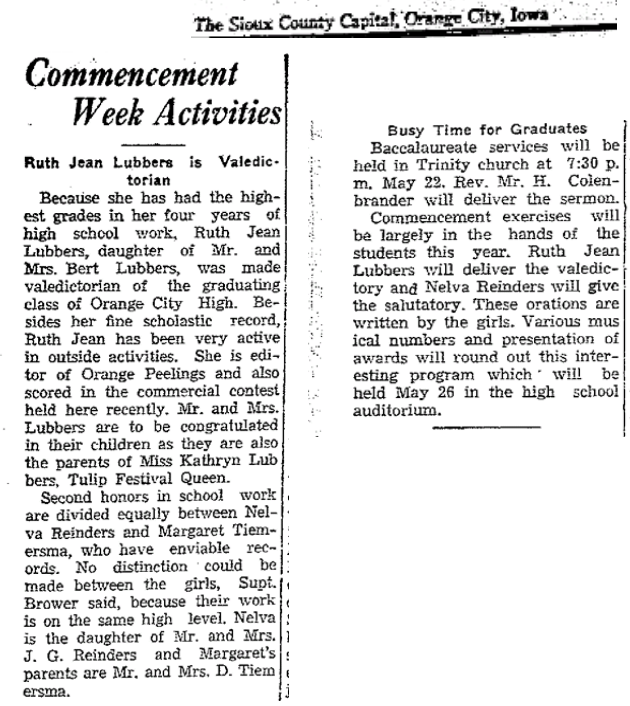

Mrs. Ruth Jeane Lubbers

On the maternal side of the family, Larry Ray’s mother, Ruth Jeane, was the daughter of Albertus “Bert” (1886-1961) and Helena Lubbers (nee Doeksen) (1888-1985). She was born in Orange City, Sioux County, Iowa, on April 23rd, 1921.

Map showing Bert Lubbers property (160 acres of land, in section 28, Holland Township). Source: Atlas of Sioux County, Iowa.

Albertus Lubbers was a farmer, born in Orange City, Sioux County, Iowa, to Dutch immigrant Roelof Lubbers (1842-1923) of Sleen, a small village in Drenthe, Netherland, and Jane Heemstra Lubbers (1849-1931) of Holland, Ottawa County, Michigan (like Pella, the city of Holland was also settled in 1847 by Dutch Calvinist seceder). According to the 1923 Atlas of Orange County, Bert Lubbers owned 160 acres of land, in section 28, Holland Township, just north of Orange City (see map above).

On the other hand, Helena’s parents (William and Treintje Doeksen) were Dutch immigrants who settled in Hull, Iowa. Helena herself was born in Friesland, Netherlands (in the village of Kinnum, on the island of Terschelling) and, at the age of six months, came to America with her parents.

We found out that Larry Ray Foreman’s genealogy contains some of Seceder’s ancestors. One of his maternal great-grandmothers, Jane Heemstra (Rodolf Lubbers’ wife) was the daughter of the early Seceder pioneer, Tjeerd Fokkes Heemstra (born on November 8th, 1824 in Hijum, Leeuwarderadeel Municipality, Friesland, Netherlands, and died on April 15th, 1901, in Sioux County, Iowa.)

In 1847, Tjeerd Fokkes Heemstra traveled to America with his Frisian Christian ‘Afgescheiden’ congregation immigration group of 50 farmers and 30 children formed in the provincial capital Leeuwarden. This group was led by Reverend Marten Annes Ypma (1810-1863), the founder of Vriesland, which today is an unincorporated community in Zeeland Charter Township, Ottawa County, Michigan. Upon arrival in America, the group settled in the city of Holland with the Van Raalte group. For details of this immigration adventure read “The Search for a Family Legend: The Frisian Background of Marten Annes Ypma, the Founder of Vriesland ” (Albert Ypma, 1997). (Note: if you skipped the historical section, you might feel a little bit lost in reading these last two paragraphs.)

Regretfully, our investigation did not produce a picture of Larry Ray’s mother, Ruth Jeane. She graduated in 1938 from Orange City High School as a valedictorian.

Ruth Lubbers was a very good student and active in extracurricular activities. Source: The Sioux County Capital of May 12, 1938.

After her high school graduation, she entered Northwestern Junior College (an institution established in Orange City in 1882 and affiliated with the Reformed Church in America; since 1961, it has been a four-year college with the name Northwestern College) where she received a two-year teaching degree. It is our understanding that she taught grade school in Orange City before the United States entered the Second World War in December 1941.

Like her husband, Ruth Lubbers Foreman also furthered her education. In 1962, she earned a bachelor’s degree in English from South Dakota State College in Brookings, South Dakota, and, in 1964, an M. A. Degree in English from the same institution (Foreman, Ruth L. An evaluation of the developmental reading program at South Dakota State College. Diss. South Dakota State University, 1964.)

Then, she pursued doctoral studies at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa where she specialized in the study of the literary works of the writer Bess Streeter Aldrich (1881 – 1954). This writer was one of “the most prominent and popular of the many “regionalist” novelists in 19th and 20th century North America” remembered by her popular book, A Lantern In Her Hand (1928). In 1982, with her dissertation, entitled, “The Fiction of Bess Streeter Aldrich,” Ruth Jeane Foreman obtained her Doctorate of Arts in English from Drake University.

Conclusions drawn from the study are that there are examples of the major literary movements in the Aldrich writing, and that they are combined to varying degrees in all of her fiction. Furthermore, Aldrich”s work has some literary merit above and beyond its historical, inspirational, and nostalgic contribution. Although none of the fiction can be classified great literature and some is sentimental popular fiction, Aldrich made a contribution to midwestern literature of the period and deserves attention (Ruth Foreman, 1982).

From 1962 to 1989, she taught English at South Dakota State University (SDSU). In the same year, when she started teaching at South Dakota State College, her son Larry Ray became a freshman at the same institution.

She also taught English in Asia (China, Malaysia, and Hong Kong). In particular, she served as an exchange professor for five months at Yunnan Normal University in the city of Kunming, Yunnan Province, China.

After she retired from SDSU, Ruth moved to Los Alamos, New Mexico. At that time, her son, Larry Ray Foreman was already a physicist working for Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL).

From the digital fragments gathered on the Web, it is possible to infer that Lester and Ruth got divorced. However, an exact divorce date could not be established (sometime between 1978 and 1981). In 1981, Jacob Lester Foreman was living in Memphis, Tennessee married to Avis Pentecost. In 1998, Ruth married geologist Daniel John Miles (1921-2016) of Los Alamos, New Mexico, who was one of the three founders of the newspaper Los Alamos Monitor.

Death of Larry Ray Foreman’s parents

Larry Ray Foreman predeceased his parents. Larry Ray’s mother, Ruth Lubbers or Ruth Foreman Miles as she was called toward the last part of her life died, at age 82, from complications of breast cancer, on February 23rd, 2004, in Los Alamos, Los Alamos County, New Mexico. Her memorial services were held at the United Church of Los Alamos.

While Larry Ray’s father, Jacob Lester Foreman passed away on January 5th, 2011, in Memphis, Tennessee. In Memphis, Jacob Lester Foreman was a member of St. Luke United Methodist Church and, for 30 years, was a member of the church choir.

For the sake of completeness, let us present again the genealogical tree of Larry Ray Foreman.

The siblings of Larry Ray Foreman

Jacob Lester Foreman and Ruth Jeane Lubbers had three children: Larry Ray (1944), Mary Ellen (1946), and Gary Bret (1955). They all graduated from Brookings High School.

Mary married John Murphy of Bozeman, Montana. She became a historian (Ph.D., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1990; M.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1983; B.A., summa cum laude, University of Massachusetts at Boston, 1977) and is presently a Distinguished Professor Lecture at the History and Philosophy Department of the University of Montana. Gary married Michelle Gaynor and lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Left: Gary Bret Foreman (1971 sophomore picture); Middle: Mary Foreman (1964 senior picture); Right: Larry Ray Foreman (1962 senior picture). Source: Brookings High School Bobcat Yearbook.

Larry Ray Foreman. Growing up in Hull, Sioux County, Iowa

As we have seen, in September 1946, the Foreman family settled in the city of Hull, Sioux County, Iowa. Very early in his life, Larry Ray began to take part in the town’s social activities. In 1948, for instance, he “spoke a little piece” at the American Legion Auxiliary meeting.

The Foreman family took part in many activities of the American Reformed Church of Hull. In 1949, when he was five years old, at the American Reformed Church Christmas observance, on Saturday, December 24th, Larry Ray delivered a “Welcome to the crowd.” In 1952, for the Sunday School Christmas Program, Larry Foreman, together with David Hesla, Merlyn DeBoer, and Lyle Kooiker, sang “Remember God’s Creatures.” and his sister Mary Foreman delivered “Hello, Folks.” For the same occasion, in 1954, together with David Hesla, David Lemmen, Merlin De Boer, Ronald Graham, and Donald Graham, he sang “Love’s Christmas Tree.”

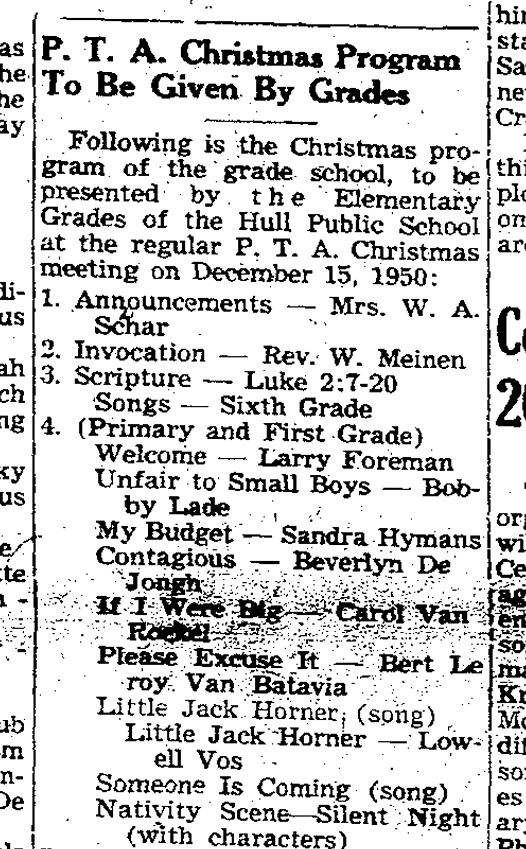

In 1950, young Larry Ray Foreman began his student life at Hull Public School. In December 1950, we already see him delivering a ‘Welcome’ at the P.T.A. Christmas program.

When Larry Foreman was seven years old, we learn from The Sioux County Index that he “had his tonsils and adenoids removed at the Hull Hospital Friday [September 28th, 1951] .”

In his professional career, as we shall soon see it, Larry Ray Foreman won many distinctions. Early on he began to win honors. On June 9th, 1955, The Sioux County Index informed us that at the Sioux County Federated Woman’s Clubs Art Exhibit, Hull Public grade school won many honors (3 Superiors, 5 Excellents, 8 Good awards), among them: Grade 5, Larry Foreman (Superior).

Because his father, Lester Foreman was pursuing graduate education during the summer, Larry Ray spent his summer vacations near the universities where his father was studying: two or three summers in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and, at least, five or six summers in Greeley, Colorado.

He also spent part of his summers with the Boys Scouts. He was a member of Scouts of Troop No. 215. For example, in August 1955, he and his troop camped out with 134 boys from Sioux and Plymouth counties.

We also know that Larry Ray socialized with Americans of Dutch descent. On April 1st, 1954, the Sioux Center News (Sioux Center, Iowa) carried the following notice: “Larry Ray Foreman was ten years old on Thursday. The following boys enjoyed a nice birthday dinner at Larry’s home: Clayton, Calvin, and Lyle Kooiker [(1945-2000)] and Merlyn de Boer [born March 17, 1944].” This same newspaper notice also mentions the Foremans visiting the Lubbers family. Clayton and Calvin are twin brothers, born in 1942, who later went into the construction business.

On another occasion, in March 1957, “Rev. and Mrs. Wm. De Jong and son, Vernon of Pella came Thursday. Mr. De Jong was a guest speaker Thursday evening at the dedication of the Parish House at First Reformed church. They were house guests at the L. R. Kooiker home. Vernon visited with his former schoolmates at school and spent the nights with Larry Foreman.”

Did Larry Ray Foreman have a Dutch-American identity?

As we stated before, this is a difficult question to answer because in this investigation we did not have access to Larry Ray Foreman’s documents conveying his thoughts and worldviews. Yet, we think we can make the educated guess that “Dutchness” had no bearing on his identity.

Larry Ray Foreman grew up in a family of Dutch ancestry, but of Frisian heritage, with values related to the Reformed Church of America. Jacob M. (Fokkema) Foreman was one of those independent-minded Frisians who dispersed themselves in America. He initially settled down in Elgin, Plymouth County and, some years later, moved to Orange City where he died. Because Frisian colonies were small they tended to assimilate or Americanize faster than other Dutch immigrants. The early transition we have seen in the Foreman family from membership in a Dutch-worshipping-language church to an English-worshipping-language church, in a way, reflects this early Americanization of the descendants of Jacob M. (Fokkema) Foreman.

Therefore, we think that the “Dutchness” of the parents of Larry Ray Foreman had already largely faded away. In addition, because of the circumstances of World War II, the parents of Larry Ray Foreman moved outside Iowa to places that were not influenced by Dutch immigration. This event should have influenced their outlook on life.

Even though, at Hull, Larry Ray socialized with young people who were also of Dutch ancestry, we think that he was just one American boy playing with other American boys who happened to have Dutch ancestry. He next spent his junior high to university years (13-22) in Brookings, South Dakota, which is a city that had little Dutch immigration.

Therefore, we guess that other than religion-related values, Larry Ray Foreman did not have an ethnic identity as a Dutch American. He probably considered himself just an American citizen with some Dutch ancestors in his family background. Larry Ray Foreman was among the first of the Foreman family to marry outside the Dutch American group.

Yet, through Jacob M. Foreman (1855-1941), Larry Ray Foreman is part of the fascinating saga of the Dutch immigration to America.

CLICK HERE TO GO TO PART II: LARRY RAY FOREMAN, THE PHYSICIST

Support for VES Project

VES Project is a Venezuelan independent research initiative with no other source of funding except for the support it receives from its readers and people sympathetic toward the project’s aims and objectives. Because living conditions in Venezuela has become very difficult and harsh, your support is now more needed than ever to help us continue doing more research and writing.

VES Project needs funding to continue researching and writing the life stories of the Venezuelan STEM migration. If you wish to support VES Project, you can use PayPal to make a donation by clicking the DONATE button below. Your help will be highly appreciated. Thanks !

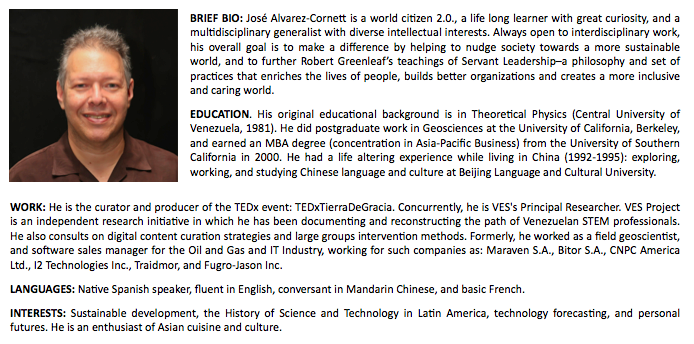

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

José G. Álvarez Cornett (Twiter: @Chegoyo)

Member of COENER, and the “Physics and Mathematics for Biomedical Consortium“. Teacher of History of Physics and Cultural History of Science at the School of Physics, Faculty of Science, Central University of Venezuela and Alumni Representative before the School of Physics Council.

@Chegoyo 2018.

Recent Comments